It is an open question who is or was the best editor in the world. For me, Juliusz Rawicz, Julek (pronounced: Yulek, it is Polish) to his friends, was the best newspaper editor I ever knew. His coworkers at Gazeta Wyborcza, the Polish newspaper, called him the world’s best editor.

My first journalistic experiences are half a century old. I studied electronics at that time. To vent my interest in politics, I started writing for the Polish students’ nationwide biweekly. A few months later, they offered me a monthlong internship at the best Polish political periodical. Editors there extended it to the whole 10 weeks of my vacations and kept me around until a year later, when the apparatchiks had enough and fired them all. In the process, my journey into journalism became a serious matter.

The historical context

At that time, Poland was a socialistic country. There was no freedom of the press. It affected writers in three ways. First, editors were asked to publish a rosy picture of the socialistic reality and avoid news and opinions suggesting otherwise. If they did not, they were fired.

Second, on top of that often vague political pressure, the censors’ office read carefully every publication before printing. Censors had very detailed directives of what could or could not be published. Certain names, facts or phrases could not even be mentioned. Some events could be reported in the middle of the paper in fine print, but not on the front page. Editors knew most of the censors’ directives and tried to be proactive; too many censors’ interventions were a way to lose a job.

Lastly, authors aware of that system self-censored their writings. In Polish, being politically correct is often expressed as sticking to a vertical line of a doctrine. We joked that it was an art to keep writing (politically) plumb while maintaining the level (of writing quality).

Such a handcuffed system never could work as intended. There always were editors and authors trying to outsmart it and wink at readers. The press cannot stay credible when devoid of all information considered arbitrarily inconvenient by the rulers; hence, it needed to maintain a space for a “constructive critique.” We called it “safety vents.” Lastly, there were differences in opinions among the ruling elite. Individuals there used their influence to advance their causes in the press.

‘Yeast’ in the Polish politics

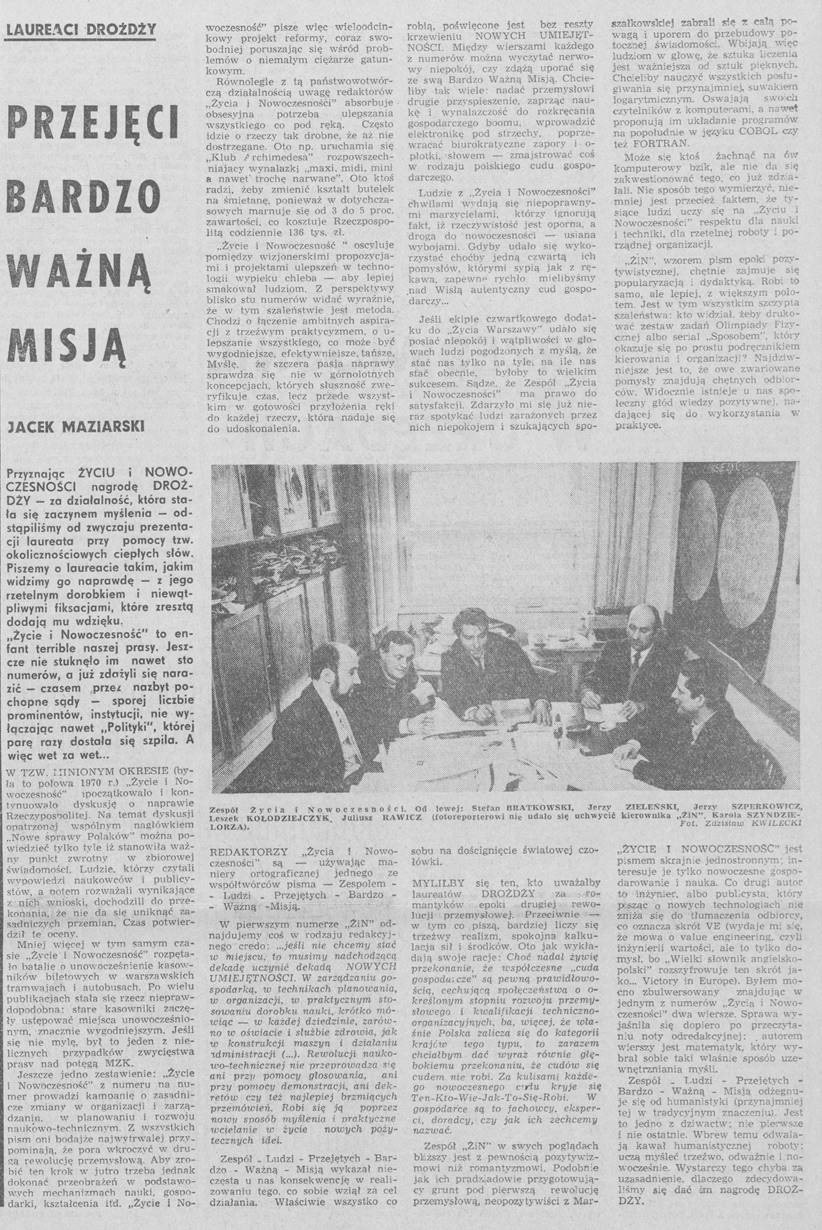

Życie Warszawy (Life of Warsaw), now defunct, was the major newspaper in the capital region. On every Thursday, there was a four-column insert called Życie i Nowoczesność, ŻiN, (Life and Modernity). For about three years (1970 -73), this tiny publication, under the leadership of its founder, Stefan Bratkowski, was the most intellectually daring in the nation.

Formally ŻiN was an apolitical forum for the exchange of ideas on how to adopt the newest inventions in technology and science to modernize the nation. The moment was perfect. A quarter-century after WWII, Poland had rebuilt, and there was a lot of joy and optimism. The baby boomers like me, mostly well educated, were entering adulthood. Computerization, which had just started, embodied the sense of great opportunities. By exploring these prospects and appealing to the energy of the youth, ŻiN brought a breath of hope that Poles could do almost anything.

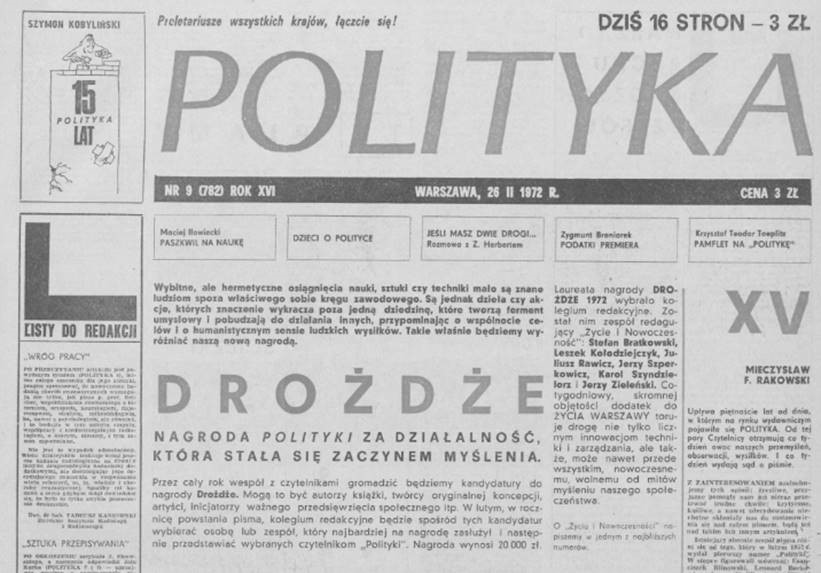

In the spring of 1972, the small team of ŻiN received recognition as intellectual “yeast” in media from Polityka, the most prominent Polish periodical. The reasoning was that it takes many ingredients to make bread, but without that pinch of yeast, the dough does not grow. They were the ones that made things grow.

In the summer of 1972, I walked into the center of it.

Julek’s dominion

Bratkowski, the founder and the team leader, still in his mid-30s, was already a figure bigger than life. Besides articles, he had already published a few popular books; he was known for his creativity and optimistic temperament. His team contained similar high achievers. The core crew was about 10 to 15 people, with a few full-time editors and a few part-time writers, including interns.

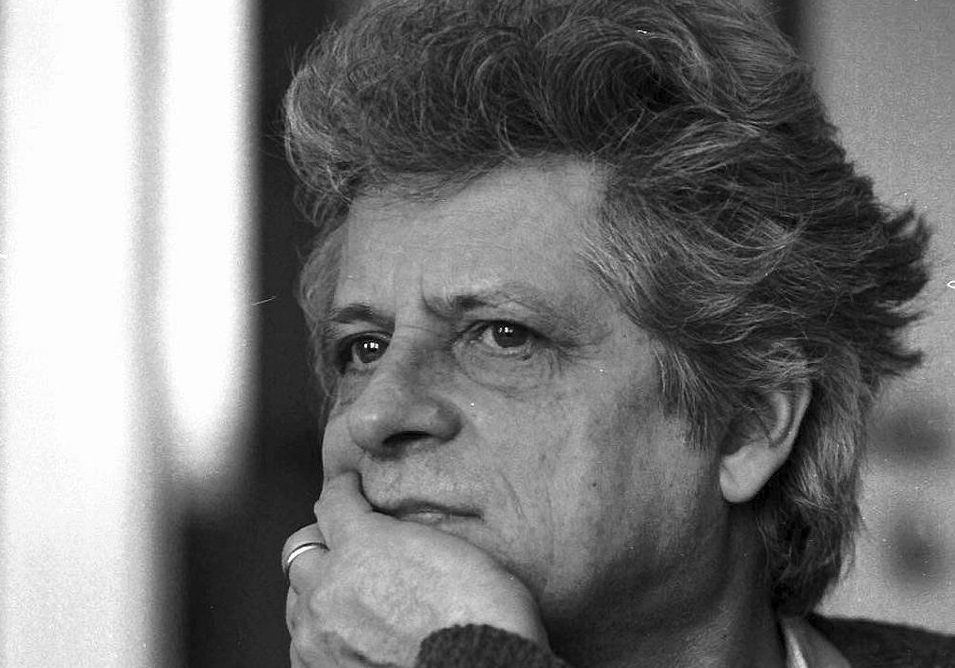

Anyone who has ever worked with temperamental high achievers knows how hard it is to manage them. The clearly defined purpose of the publication and its spectacular success mitigated those passions, but sparkles were a daily routine. Julek, shorter than most, with an unintimidating posture and a disarming smile, was the glue holding the team together.

Julek’s dominion was not impressive. Six worn-out desks clustered in one room, with barely any space to pass. Julek was the editor at large, the only one who was not a writer. During the meetings, usually, with about 10 people attending, most of us were standing or sitting on desks, almost touching each other. The door was always open to the hallway where other offices of Życie Warszawy were located. The door had been closed only for short periods when discussions turned loud and unruly.

Julek’s drawer

Publishing good articles was not the goal. They were on the mission to modernize Poland. The staff identified issues important to readers. When getting a manuscript addressing an important issue, they looked at how it related to articles published before, and other aspects and related views. Often, someone from the team had some expertise and interest in writing another article on the subject. Then, Julek was asked what he had in his drawer.

Julek, a working bee, scrupulously reviewed every submission and kept in his drawer manuscripts with some potential. As a result, readers received a comprehensive set of articles about the subject in question, often with brief editorial notes. Accustomed to being lectured, readers found it refreshing to receive multifaceted information and left to make their own judgment.

A relentless hunt for talent

A few days into my internship at ŻiN, they accepted my first submission and, soon after, the second one. I was happy, but it felt uneasy for me to see how much other team members were excited about my success. It took me a while to realize that they were not celebrating my success; they expressed their joy at capturing a new talent.

Stefan repeated almost daily that we had several people employed, about 100 regular contributors, and more than 1,000 experts writing occasionally. In his view, that broad spectrum of contributors was the core of the value that ŻiN offered its readers. It stuck in my memory how often Stefan bragged about bringing an excellent article from an unknown author.

Criteria for acceptance of texts

I mentioned earlier the team’s excitement with the publication of my first text. By the end of the day it was published, I was just about to leave when a former intern and an aspiring writer walked in. He had degrees in Polish literature and journalism; I was just a student in an engineering college. Hence, I was curious about his opinion. I was genuinely happy when he said that he had found a serious problem. Then he started talking about a syntax issue in one of the sentences in my article. I reread that sentence and could not see a problem. Julek, diplomatic as always, said that it was not a big problem. Then, I asked this fellow if he had comments on the merit of my article. He insisted that writing correctly in Polish was crucial. I thanked him and left because the more he talked, the less I could understand, as my Polish language education ended in high school.

My friend who stayed in the room told me later that after I had left, that fellow intensified his critique of the sentence in question. The chief editor cut him short: “We do not publish Mr. Henryk for the excellence of his grammar but for what he has to say. For grammar, we have editors.”

It took me a while to realize how deeply this reflected the mission of ŻiN. One morning on Julek’s usually empty desk, there was a manuscript. At that time, anyone from the street could walk into our office. We guessed it was a submission, and Julek asked me to review it. I started by noticing that there was no title nor an author’s name. Then, in the first paragraph, punctuation was missing, and I found a few spelling errors. Julek smiled. He recognized the author, who writes that way, but “he has some good ideas, and we publish him sometimes.” That manuscript went into Julek’s drawer.

On another occasion, Julek tasked me with condensing to five pages a 15-page-long manuscript poorly written by a university professor. It was about the advantages of the trimester system over the conventional two semesters. This way, more baby boomers could get an education in the same buildings. The professor approved the edit, and ŻiN was the first mainstream media publication in Poland to introduce the trimester concept. Being the first with a new idea was far more critical than the quality of writing in the submission.

In my second stint as an intern during the 1973 vacations, Julek trusted me more to work with new submissions. I spent hours talking with all sorts of strangers, realizing how hard it is to find people who have something original to say. It surprised me how many trained young journalists had all the technical skills to write the best articles in the world but were devoid of critical thinking. They were infatuated with getting their name in print in a major newspaper, but they could not figure out why I was not impressed with their submissions. They had nothing original to say.

Authors are the stars; editors are promoters

Working with Julek was fun, but not for everyone. It was easier for me because I clicked with the team quickly. Julek was a language purist, meticulously polishing all imperfections. My prior experiences were with editors in a student periodical who were self-taught older colleagues. Often, I questioned their interventions, accusing them of butchering my articles. The most annoying was the tendency to add their ideas to twist my message.

I looked over Julek’s shoulder with the same combative attitude when he was editing my first few submissions. He was crossing out a few words, a line, or the whole paragraph, praising the text and adding comments such as: “it sounds better without this,” “you said it better a few lines above,” or “this is an unnecessary distraction.” To my disbelief, I agreed with his changes. He took time to understand the author’s message and then used his craft to master the delivery.

Working as Julek’s assistant, I realized that superb editorial work is crucial to the success of any publication. Very few authors have the skills, discipline, and patience to bring their texts to perfection as editors like Julek could do.

A few years after being fired from ŻiN, Julek got a job with another reputable publication. They published my articles. But there was one piece they had not used for a few months. On one occasion, I asked Julek if it was not good. He claimed it was OK, but he was waiting for the right moment to publish it. But when I pushed a little, he acknowledged, “We got used to getting better texts from you.” He never published that article. I think about this incident whenever I read columns by renowned authors in reputable publications which do not have editors equally good as Julek was.

An editor needs to separate wheat from weeds

One may say that all editors do their best in selecting good texts for publication; hence, there is nothing special about the way we did it at ŻiN. The key is in distinguishing the wheat from the weeds. In the case of a political publication, it is even harder because we all have our ideological leanings, and some differences of opinion probably will never be resolved to the end of our days.

A cheap shot for many editors is in associating a publication with this or that bias. Usually, it is called a noble mission of spreading ideas that matter. Readers may cluster around publications they identify with, but even the most zealous ones occasionally can see the lack of objectivity. The skeptic would trust no one.

The success of ŻiN was in doing for the readers what most of them had no time and resources to do themselves. Editors identified issues of public concern, and then in front of their readers, they looked for workable solutions. They asked and tried to answer questions that most readers had. What are the experts saying, what are historical analogies, how did others solve similar problems, and are there any new technological or scientific advances? To do it competently, they needed to be intellectual giants. They were. Besides having an expert knowledge in some areas, they all were erudite.

Julek was known for his encyclopedic memory. Whatever the issue was, he could recall a book about it, an article, a scientific study, or a historical fact. I was an avid reader interested in a broad spectrum of subjects, but next to Julek, I felt like I barely read anything.

ŻiN was an insert in the daily newspaper. On every Thursday, they sold 450,000 copies. About one million people had our publication in their hands for at least a minute. It was up to us to make that reader spend more time on our pages. They were academics, line workers, and everybody in between. The ongoing mantra in the editorial room was that someone with only a grammar school education should be able to understand our articles, but a university professor should find them worth reading as well.

The influence of ŻiN was increasing. It became too troublesome for the apparatchiks. By the fall of 1973, they fired the key people at ŻiN. A few writers got a so-called “wolf ticket,” which was a notification to the censors’ office that no one should publish any writing by that person in the whole of Poland.

Under the new docile leadership, ŻiN lost its appeal. But the genie was already out of the bottle. Journalists in Poland felt the power of the written word. About 100 of them, including me, experienced that personally. Many Poles saw more clearly the political system’s infirmity and realized that things easily could be better with a little common sense. In the following years, Solidarity burst out. The Soviet Union was due to collapse for its own reasons, but events in Poland triggered its demise. For their determination to advance Poland, the editors at ŻiN were recognized as yeast. They lost their jobs, but the leaven they sowed can be traced to the events that changed the world.

The future has the great past

Erudition has consequences. One of the most common illusions of dunces is believing that our times are exceptional, and that whatever happened before is irrelevant. The more we know about the past, the more we realize that everything has already happened before. The technology has changed, but human nature stays the same for millennia.

Bratkowski’s favorite motto was that the future has the great past. Whatever problem we face today, in some variation, it has already been resolved for better or worse by someone. By knowing the past, we can be smarter in shaping the future.

In that spirit, I share my experiences, which occurred before many readers of this article were born. I hope that what I learned can inspire others today, when we have so many controversies and a lot of confusion about the print media.

Many tell us what to think. I ask my readers to be skeptical. Question me and others.

Many tell us what to think. I ask my readers to be skeptical. Question me and others.