or what do they not teach at the University of Illinois Chicago?

At the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) Law School, professor Jason Kilborn (the links are references for inquisitive readers) is not teaching during the spring semester of 2022. His classes have been canceled or reassigned. Instead of teaching, professor Kilborn will be taught racial sensitivity at the five-module course. After each module, he shall write a self-reflection paper. Additionally, according to the letter from the UIC legal counsel, John B. Alsterda, “the Law School (at UIC) is retaining an instructional advisor to work with professor Kilborn one-on-one.” The “goal is to return professor Kilborn to the classroom.” This means that returning to teaching in the fall semester is still up in the air.

On the website rating professors, one should look for opinions posted before the current controversy. Most of the reviewers call professor Kilborn “awesome,” very knowledgeable, someone who could be “hilarious” and shows some leniency in grading. Critics did not like his temperament, saying he talks too fast, does cold calling in the class, and makes unprepared students feel dumb. He is a professor cherished by students who “want to learn and are ready to do work,” as one commentator wrote.

Jason Kilborn started teaching at the John Marshall Law School (JMLS) in 2007. For the record, in 2019, the school merged with UIC. In 2021, the name was changed to the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law. Dropping “John Marshall” from the school’s name was one of the demands of people who filed complaints about professor Kilborn with the school administration.

John Marshall was the fourth chief justice of the Supreme Court (1801–1835), credited with establishing it as a verifier of the constitutionality of the laws implemented by Congress. We know it today as the third branch of the federal government. Like many affluent people in his time, Marshall owned slaves. Some black students claimed that “keeping ‘John Marshall’ in the law school’s name honors this nation’s racist history.”

From 2007 to mid-2020, professor Kilborn had an excellent reputation. The complaints started at the end of the spring semester of 2020. They happened in connection to the things that the University of Illinois Chicago fails to teach.

They do not prepare their students for life in the real world

Professor Kilborn is in trouble because he stands for the opposite.

During the spring semester of 2020, when Covid-19 unwound, professor Kilborn encouraged students to attend classes but accepted remote video participation and expected completion of the assignments. A few students fell behind, but professor Kilborn followed up with emails. Eventually, except for one, they all met the minimum criteria required to take the final exam. One student did not respond to any of the professor’s emails until receiving a notification of being dropped from the class. Then, that student asked for one more chance. Professor Kilborn gave him a simple assignment requiring not much work but trying to ensure a commitment to catch up. In the follow-up investigation, everyone agreed that the subsequently submitted work was “woefully deficient.” The student in question was dropped from the class. He learned that when not meeting specific deadlines such as those faced by a lawyer in real life, he would fail his clients.

They do not teach that at UIC; the dropped student filed a formal complaint with the Office for Access and Equity (OAE) at UIC, claiming discriminatory treatment because of being black. The identity of that student stays secret, despite the fact that his claim was rejected as bogus.

So why is professor Kilborn in trouble? Another professor at UIC intervened on behalf of that student. In the investigative report, that professor’s name is concealed as Faculty A. But on page 17 of the report, Faculty A is identified as “head of SCALES program.” After a few clicks on Google, one can find out that the identity of Faculty A is professor Samuel V. Jones.

Professor Kilborn rebuffed the intervention of professor Jones on merit, to protect the student’s privacy, and because professor Jones had no authority for such intervention.

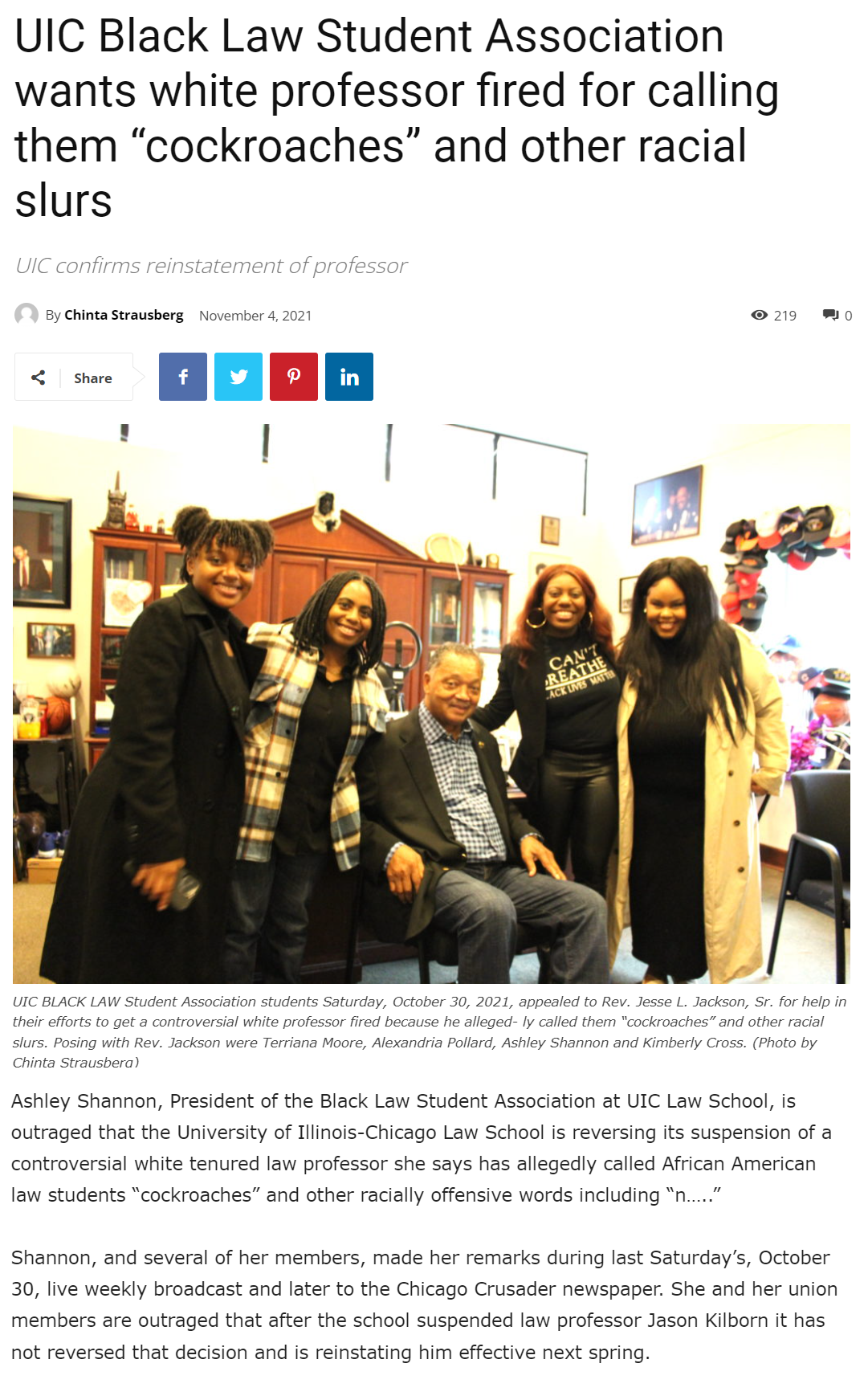

Readers who click on the link can see that professor Jones is black. The curious ones can find his latest article where he states as an axiom, not requiring any proof, that there is “anti-Black racial harassment on law school campuses.” He asks for “cultural competency,” which in his paper is a synonym for the political reeducation of white people. It looks like professor Jones picked professor Kilborn to practice what Jones preached in his treatise. On this mission, he worked with a few other students from the UIC Black Law Students Association (BLSA) on building a case proving supposed racial insensitivity in professor Kilborn’s lectures.

One of the complaints was that in the exam, professor Kilborn asked students about the labor law case where a person quit after “Plaintiff, calling her a ‘n____’ and ‘b____’ (profane expressions for African Americans and women).” That is literally from the exam. The same question was on exams for about 10 years, but in 2020 that question caused an uproar. Some black students felt offended, got heart palpitations, and were mentally distressed.

Professor Andrew Koppelman from the Northwestern University School of Law wrote two articles about professor Kilborn’s case, not mincing any words. He called the whole affair a witch hunt, with the investigation butchered, and reminded the administrators at UIC that “If lawyers are going to be competent to do their jobs, they must be able to cope with the fact that humans sometimes do and say very bad things.” Frankly, more often than not, offensive words are not the worst things people do. But preparing students to function in the real world is not the aim of the leaders at UIC.

They do not teach the law

They have classes that teach the laws and court cases. But they do not teach about the rule of law. People learn the rule of law not from books or lectures, but by observing how it is practiced toward them and others.

Professor Kilborn followed the school’s rules by dropping the student, as required for law students, as needed for the school’s accreditation by the American Bar Association. Now, when the school determined with no doubt that the complaint by that student was unsubstantiated, one might have expected that UIC would have investigated whether, by filing a bogus grievance, the student and professor Jones, in supporting the student, had not broken the law. If UIC has done that, it has not become public yet.

Besides the case of that student, a group of black students from the Black Law Students Association, together with professor Jones, filed a complaint claiming that professor “Kilborn’s harassing conduct has created a racially hostile environment for Non-White students.” The quotation is from the findings by the OAE, which agreed with the complainants on this allegation.

Besides the aforementioned exam question, there was not much evidence. The accusers and the OAE put hours of work on vivisecting the seconds-long descriptive comment by professor Kilborn during the lecture on January 23, 2020. Professor Koppelman heard the full recording of that lecture and claims that there was nothing inappropriate in it. From my reading, when explaining frivolous lawsuits, professor Kilborn argued that the most sensational of the successful lawsuits lose on appeal, but the media publicize the spectacular victories, thereby encouraging others, and then “cockroaches” come out and do the “lynchings.” Some black students found both terms offensive.

From the sidelines, the sensitivity to “cockroaches” brings to mind a story of a young woman who felt uncomfortable when a boy whistled a lewd song on their first date. As for lynching, it was a part of American culture not that long ago. Not always, blacks were around. In particular, Robert Paul Prager, an American of German descent, was lynched in Collinsville, Illinois, on April 5, 1918. A few days earlier, someone in the community overheard a comment of his that was considered unpatriotic. In 1917, the United States had joined WWI, fighting against Germany. Thus, in Illinois, Americans of German descent can also be sensitive to the term “lynching.” The oversensitive black students did not know that. They joined academia to teach professors, not to learn from them.

I am elaborating on that petty issue because Ashley Davidson (no longer with UIC), who investigated the case and prepared the report, presented a shaky theory that besides compliance with applicable laws, the obedience of school policies should be a factor in determining if racial harassment occurred. She writes that “a Policy violation may be found even where the harassing conduct does not constitute a violation of applicable legal standards.” What she did not write explicitly, but implied and exercised in the investigation, is the assumption that the standards and protocols used in enforcing the law do not apply in the enforcement of policies.

Here we arrived with the next thing they do not teach at UIC.

They have no respect for personal integrity

We all intuitively know the rules of law. Everyone is presumed innocent until proven guilty; we have the right to face our accusers, present our defense, and expect that our unbiased peers will decide if the wrongdoing occurred. For the regulations issued by government agencies, we have detailed judicial procedures guaranteeing the rule of law.

Similarly, as UIC has its policies, we all are subjected to the myriad of policies at our workplace, at the condominium association, at the social organizations we belong to, and at the store, museum, theater, or any other place we might visit. It is impossible to follow the formal judicial protocol in resolving all claimed wrongdoings in those everyday, often trivial situations. But people with administrative authority need to resolve millions of these petty claims every day.

A person with personal integrity handles these cases following the aforementioned rules. That person attempts to get all the relevant information, makes sure that both sides present their case, and includes persons sympathetic to opposite sides in the decision-making if there might be any concerns about bias.

Before investigating the Black Law Students Association complaint against professor Kilborn, Ashley Davidson was the president of BLSA at the Illinois Institute of Technology Chicago-Kent College of Law in the years 2017–2018. A basic sense of decency would require Ms. Davidson to exclude herself from this case presented by her buddies from BLSA.

She did the opposite; she took advantage of her position to transfer the zealous tone of the accusers into the report from the investigation.

Ashley Davidson could not do it alone. There is no way that professor Jones, supporting the accusations, did not know about her conflict of interest. He should know better. If he had any personal integrity, he would have requested the exclusion of Ashley Davidson and the inclusion in the investigating team at least one person representing professor Kilborn. They did not care about details such as the truth, or creating at least the appearance that the administrative investigation followed the fundamental standards of the rule of law. They did not worry because the investigation was conducted in secrecy. Professor Kilborn learned about it post-factum. It took a freedom of information request to make the investigative report public.

The investigative report elaborates on the factual and potential emotional distress of non-white students resulting from the assumed racial insensitivity of professor Kilborn, but it nonchalantly dismisses the harm that the phony accusations and the entire process caused to professor Kilborn. Even worse, the complaints of professor Kilborn pointing to the ridiculousness of the allegations and to the unfair process are used in the report as supportive arguments of his presumed racial bias.

Donald Kamm was the immediate boss of Ashley Davidson. He needed to approve keeping the investigation secret. If he did not know about Ashley Davidson’s conflict of interest, it was his job to find out. If he read her report before approving it, he should have at least become suspicious about its fairness. It is even worse if he approved that report after reading it.

On November 30, the school leaders approved the results of the investigation. Michael Amiridis, chancellor of UIC; Javier Reyes, provost and vice chancellor for academic affairs; and Julie Spanbauer, interim School of Law dean, signed the statement posted on the UIC website. This means that the lack of personal integrity at the University of Illinois Chicago is systemic; it goes from the top to the bottom. Professor Kilborn missed the memo and got in trouble.

For the record, on January 15, 2022, Michaels Amiridis was nominated to be the next president of the University of South Carolina.

They do not teach the academic method

A skeptic may say that whites might dismiss as unreasonable the complaints from black students, who would argue that unless one is black, there is no way to know how harmful and undignifying some seemingly innocent behaviors can be. They may argue further that instances of racial harassment that are reviewed with participation by presumably privileged whites can never lead to any improvements. From there, it is not a big leap to the conclusion that seems to be behind the arguments of professor Jones, that without applying political power, the racial disparities never will be resolved.

One can question that reasoning on merit, but let us put it aside. Using political power to resolve problems is acceptable everywhere but in academia. Teaching is not the main purpose of universities. First and foremost, they are intellectual mills; the truth is their product. Their job is to deploy the academic method, also called the scholarly method or the Socratic method, to search for the truth.

That approach did not cross the minds of anyone at UIC except professor Kilborn. Seeing the absurdity of the accusations, he naively thought that he could overcome the charges by presenting rational arguments. No one cared to hear his reasoning, but every time he opened his mouth or wrote an email, his opponents scrutinized his every word and displayed a lot of creativity in twisting what he said/wrote to form more accusations.

America has a history of racial inequality. We have done a lot to overcome that, but we cannot change one thing: Black people always will be black. It seems that, for some, race is the dominant factor in their attitude toward others. We have many very successful black people; hence, one can ask if the racial biases of the few deprive the genuine chances for the social advance of blacks. Commenting on the case of professor Kilborn, professor John McWhorter, who is black, wrote: “Normal people don’t fall to pieces when seeing ‘n*****’ on a piece of paper, regardless of their race. The neoracists who have barred Jason Kilborn from campus in pretending this isn’t true are operating upon an assumption that black people are morons.”

The lingering racial tensions are only one of many problems that the United States faces. Immigration and health care come to mind, so too do public finances, climate change, and crime. We cannot resolve these problems by political arm wrenching and back stabbing as happened at UIC with professor Kilborn.

If the University of Illinois were the real academia, the problem brought by the dissatisfied black students would be publicly put up for academic discussion. It is very unlikely that the advocates of the extreme positions would be satisfied, but the mutual understanding would improve, and some community standards would emerge.

It did not happen.

Professor Brian Leiter, from the University of Chicago, who is a renowned authority in jurisprudence, asked for withdrawing accreditation for the UIC School of Law after learning about the case of professor Kilborn.

The proper solution may need to be more drastic than professor Leiter suggested. One should ask whether an academic institution deploying political tactics instead of the academic method in the search for the truth deserves to be called a university. I can already hear a choir of “rational” voices that the University of Illinois Chicago is not much more politicized than most other academic institutions in the United States of America. The response is that we cannot fix all of academia at once, but we have to start somewhere.

Many tell us what to think. I ask my readers to be skeptical. Question me and others.

Many tell us what to think. I ask my readers to be skeptical. Question me and others.